By Anne Vestergaard, Luisa Murphy, Mette Morsing, & Thilde Langevang

Global expectations are high for cross-sector partnerships to solve the world’s grand challenges such as poverty, climate change and inequality (e.g. WEF January 2020, UN Sustainable Development Goal 17). Our novel research findings from our study of a north-south cross-sector partnership between a Danish jewelry company and a local NGO in Ghana challenge these expectations. We particularly call attention to how the focus on ‘outcome’ has overshadowed the lack of research into local ‘impact’.

In our paper, we show how, at first glance, the ten-year-old African-European cross-sector partnership appeared to embody ‘best practice’ in alleviating poverty and advancing sustainable development. Young single mothers had been employed over the years by the European business with European governmental start-up support. The women received training to work for the partnership and education on health issues. It was competitive to get a job in the partnership and the villages perceived it as a prestigious accomplishment. The women travelled to the building, which was owned by a local NGO, and worked at the same table assembling the jewelry in the designed styles, talking and laughing.

We then discuss how, after more visits and research, we started to experience some of the limitations of cross-sector partnerships. While the partnership provided training, new resources and knowledge to the young single mothers, it importantly failed to generate the conditions to significantly bring positive lasting changes into their lives. The women had to travel far by a costly bus to work in the NGO building, leaving their children behind in the villages. Besides the children being without their mothers all day, their absence in the villages inhibited traditional practices of work sharing and knowledge exchange with family members and the wider community. The partnership relied on an old local craftmanship that was modified, via the Danish business partner, to fit European standards. Instead of the handicrafting women engaging in the product development, all product design was decided and directed by the European entrepreneur. The young mothers were left with the task of adapting and imitating rather than innovating. Additionally, only the most capable young women, the ‘viable poor’ (Blowfield & Dolan, 2014), were offered work with the partnership. This systematically excluded the poorest young single mothers in the villages. On top of that, income for the young mothers was unstable due to fluctuations in European demand for the jewelry, making it impossible for the women to plan ahead and to improve support for their children’s schoolwork.

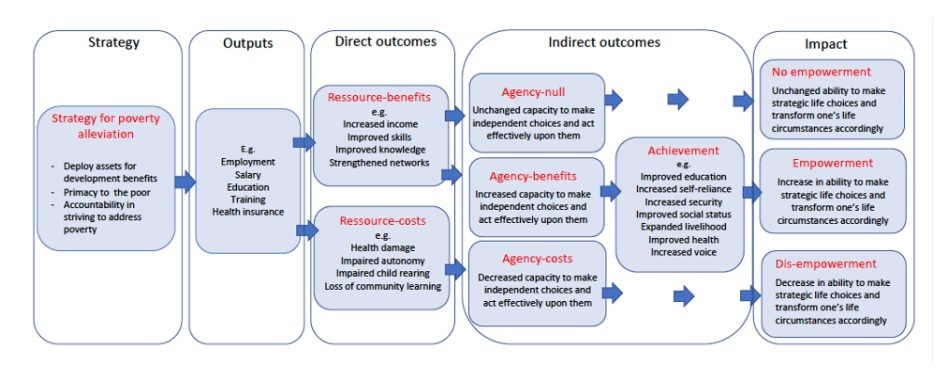

Most importantly, our findings show that the cross-sector partnership did not deliver the impact it anticipated. Those beneficiaries, who were believed to benefit from the partnership, were in fact not empowered or better off in any social or economic sense leading us to develop a new conceptual framework advocating ‘impact as empowerment’ to advance a more encompassing assessment of cross-sector partnerships as development agents.

We hope that our findings and our conceptual model will inspire future cross-sector partnerships to pay more attention to impact and not only the output they deliver by from the onset of a partnership considering what kind of impact it strives to achieve and systematically follow up to assess if that impact is in fact achieved. We also hope that future research will further explore some of the unintended consequences of cross-sector partnerships and how these can be avoided by careful and systematic follow-up where outcome is distinguished from impact in the cross-sector partnership.

References:

Blowfield, M., & Dolan, C.S. 2014. Business as a development agent: Evidence of possibility and improbability. Third World Quarterly, 35, 22-42.

Vestergaard, A., Murphy, L., Morsing, M., and Langevang, T. 2020. Capitalism’s new development agents: A critical analysis of North-South CSR partnerships. Business & Society.