By Lori DiVito

To tackle long term sustainability issues, such as poverty, climate change or biodiversity loss, requires multiple stakeholders in cross-sector partnerships (CSCs) to collectively align interests and act together. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the effects of climate change, with extreme high temperatures breaking records in the west coast of the USA and Canada and in Southern Europe. In California, a state that supplies the US with one-third of its vegetables and two-thirds of its fruits and nuts, drought is persistent. The California Water Action Collaborative, a CSC of farmers, companies, citizens, and governments work together to address water scarcity and secure sustainable and safe water supplies to multiple societal stakeholders – people, businesses, farmers, and nature.

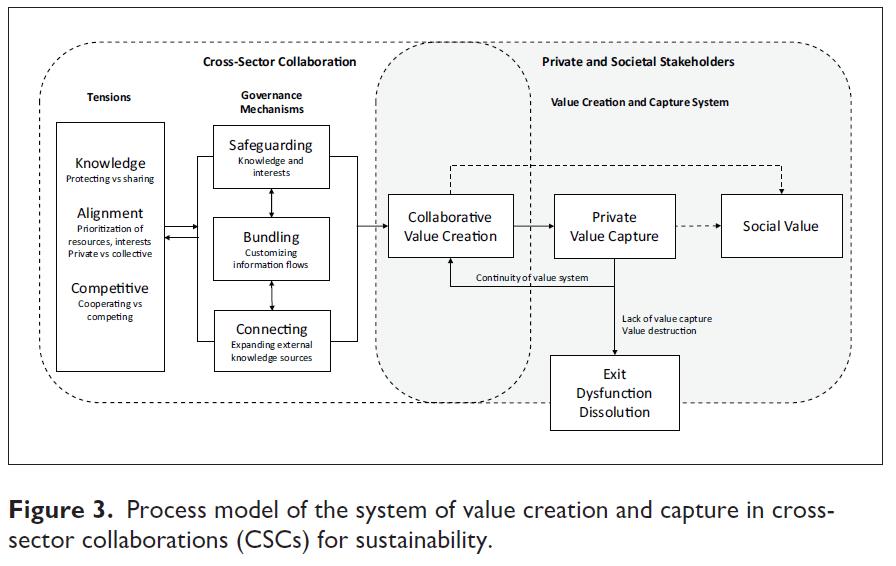

Achieving results from such cross-sector collaborations (CSCs), however, is a complex process of negotiation, compromise, and action. CSCs are multi-stakeholder collaborations between private (companies), public (government), and societal organizations (NGOs). Our paper in the special issue of Business & Society takes an in-depth look at a CSC in the textile industry and how it is governed to achieve its collective goals. As CSCs are generally not formalized companies or legal entities, different tensions, like time or budget constraints, competing interests, or an unwillingness to share information, can arise and prevent progress. Someone needs to take control and orchestrate members and participants. Drawing on the business model concept, we engaged in participatory process research for a period of two years and unpacked how CSC orchestrators govern collaborative value creation and private and social value capture.

We observed three governance mechanisms used by orchestrators to navigate tensions in collaborative value creation. First, orchestrators safeguarded proprietary/sensitive information. For example, to make progress in reducing the use of toxic chemicals in garment production, companies were reluctant to share their ‘secret recipes’. Orchestrators gathered this information but did not distribute it to the CSC members. Secondly, orchestrators bundled information (e.g., specifications for collectively produced fabric) to make it more general for collective decision making. Lastly, orchestrators also connected and matched members to participants outside and inside the CSC (e.g., suppliers or experts). Through these governance mechanisms – safeguarding, bundling, and connecting – the orchestrators built deep, unique knowledge of each CSC member and were in a unique position to steer the CSC towards goal achievement.

While collaborative value creation lies within the boundaries of the CSC, value capture lies outside. Private value capture refers to a member’s ability to capture value from the collaborative value creation. We observed value creation as a collective act and value capture as private act, dependent on the member’s organizational or individual readiness to learn and gain benefits from the CSC. We also observed that in the absence of private value capture, members were likely to lose interest, disengage and exit the CSC, jeopardizing value for society. This implies a formidable challenge for orchestrators: to ensure continued collaborative value creation, members must privately capture value, yet private value capture lies outside the span of orchestrator governance or control.

While collaborative value creation lies within the boundaries of the CSC, value capture lies outside. Private value capture refers to a member’s ability to capture value from the collaborative value creation. We observed value creation as a collective act and value capture as private act, dependent on the member’s organizational or individual readiness to learn and gain benefits from the CSC. We also observed that in the absence of private value capture, members were likely to lose interest, disengage and exit the CSC, jeopardizing value for society. This implies a formidable challenge for orchestrators: to ensure continued collaborative value creation, members must privately capture value, yet private value capture lies outside the span of orchestrator governance or control.

We suggest that besides using the above mechanisms to manage CSCs, orchestrators should also adapt the use of the mechanisms depending on the emergence and disappearance of tensions. For example, a new CSC may need to use safeguarding for managing tensions around the alignment of interests. As the CSC progresses, however, safeguarding may be less necessary. Orchestrators should also pay attention to the individual needs and beneficial outcomes (i.e., private value capture) of the members. By keeping track of private value capture, orchestrators can intervene and ensure the continuity of the CSC.

References

DiVito, L., van Wijk, J., & Wakkee, I. 2021. Governing collaborative value creation in the context of grand challenges: A case study of a cross-sectoral collaboration in the textile industry. Business & Society, 60(5): 1092-1131.